Okay so, I won’t lie to you. (With a few slight adjustments) I turned this in as a final paper today. The life of a communication arts major isn’t too bad. I was given a list of classics and told to pick one to write an “analysis essay” on, minimum five pages. So I said “Great, I’ll be able to post it on my blog after I turn it in!” And without further ado, please enjoy my analysis of the scare factor of Jaws, and the relevance of Spielberg’s directing choices to audiences today.

Okay so, I won’t lie to you. (With a few slight adjustments) I turned this in as a final paper today. The life of a communication arts major isn’t too bad. I was given a list of classics and told to pick one to write an “analysis essay” on, minimum five pages. So I said “Great, I’ll be able to post it on my blog after I turn it in!” And without further ado, please enjoy my analysis of the scare factor of Jaws, and the relevance of Spielberg’s directing choices to audiences today.

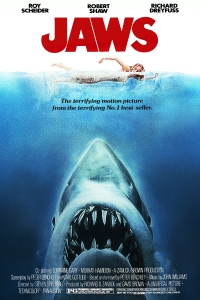

When Jaws was released to audiences in the summer of 1975, the theaters were flooded by 67 million Americans, which classified the film as the first ever summer blockbuster – due to production delays, it got pushed off of it’s estimated Christmas of 1974 release, and put in the summer slot as a gamble. Until 1975, movies that were released in June or July were more like sloppy leftovers than main dishes, and then Jaws made a solid $60 million that summer. It didn’t take long for the movie to find its niche in Hollywood history; the theme song is now iconic, the animatronic sharks were revolutionary, and the concept was terrifying.

When I first watched Jaws, I laughed my butt off for a good chunk of the movie (that sentence is not adjusted, I turned in my essay like that). I knew that the tuba meant that the shark was coming, the effects were horribly fake, and I’d seen better acting in my high school’s production of Fiddler on the Roof. However, I did get a bit of a chill when the bloody raft washed up on shore, and my head about hit the ceiling when the water-logged corpse came out of the shipwreck. There are a lot of things about Jaws that are no long relevant or scary to today’s viewers, but certain aspects of the movie are universally frightening and will forever keep the movie in the ranks of classics.

The first thought anyone has when they hear the word “jaws” is that oh-so-famous music. There isn’t a movie or TV show that’s been made since 1975 that’s shown someone in a shark-ish situation that doesn’t at least sneak a little bit of Jaws-esque music in there. Some steal it outright. It’s the universal shark-attack song, and a lot of times even gets used to mislead the viewer; if you hear the music, you assume it’s a shark, but it’s actually just a dolphin, or a kid with a fin strapped to his head.

When I was in middle school, my band director (who loved to tell vaguely relevant stories to kill extra time in class) told us about the first time he saw Jaws, when it came out in the theaters – he was in fact one of the 67 million. He described to us a theater full of people, on the edge of their seats, waiting for the infamous shark to appear. With much grandiose, he told us that the second that theme started to play, everyone in the theater whispered “Shark!”, even though they didn’t see the monster for the majority of the movie (a point we will address later). Although he had a habit of exaggerating for a good story, I do believe that what he told us was true to a certain point. The great suspense of this movie is rooted largely in the simple, two-note theme that John Williams concocted to build and build for the entire movie. And, even more effective, the climax of the movie happens when the shark appears without musical introduction of any kind. I believe a sign of Steven Spielberg’s brilliance as a director resides in his use of contrast – by teaching the audience that the shark is always accompanied by the scary theme song, what better way to scary their pants off than by giving them the shark without the theme song?

When I was in middle school, my band director (who loved to tell vaguely relevant stories to kill extra time in class) told us about the first time he saw Jaws, when it came out in the theaters – he was in fact one of the 67 million. He described to us a theater full of people, on the edge of their seats, waiting for the infamous shark to appear. With much grandiose, he told us that the second that theme started to play, everyone in the theater whispered “Shark!”, even though they didn’t see the monster for the majority of the movie (a point we will address later). Although he had a habit of exaggerating for a good story, I do believe that what he told us was true to a certain point. The great suspense of this movie is rooted largely in the simple, two-note theme that John Williams concocted to build and build for the entire movie. And, even more effective, the climax of the movie happens when the shark appears without musical introduction of any kind. I believe a sign of Steven Spielberg’s brilliance as a director resides in his use of contrast – by teaching the audience that the shark is always accompanied by the scary theme song, what better way to scary their pants off than by giving them the shark without the theme song?

This is my favorite thing about Jaws: everything brilliant about the effect of the shark’s absence was a complete cover-up for the fact that the shark didn’t actually work until the end of filming. Steven Spielberg’s pet project – Bruce, as he affectionately was named after Spielberg’s lawyer – was a complete train-wreck. The animatronics worked on land, but the whole ocean thing wasn’t taken into account until they tried to use the shark and it sunk to the ocean floor. It had to be retrieved by a diving team. After they worked the floating part out, they still had to get the jaw to close right, the eyes to stop going crossed and the body to move like an actual living thing. To compensate for a lack of shark, the film crew used water-level shots from the “shark’s perspective”, and some live footage of real sharks. Then in the final “battle” scene, they finally had a working shark. But, as I said before, animatronics are not so revolutionary nowadays. Today we can animate a shark that might as well be on the other side of the aquarium glass, it looks so real (even Sharknado looked better than old Brucey). But at the time, that shark was pretty darn impressive.

This is my favorite thing about Jaws: everything brilliant about the effect of the shark’s absence was a complete cover-up for the fact that the shark didn’t actually work until the end of filming. Steven Spielberg’s pet project – Bruce, as he affectionately was named after Spielberg’s lawyer – was a complete train-wreck. The animatronics worked on land, but the whole ocean thing wasn’t taken into account until they tried to use the shark and it sunk to the ocean floor. It had to be retrieved by a diving team. After they worked the floating part out, they still had to get the jaw to close right, the eyes to stop going crossed and the body to move like an actual living thing. To compensate for a lack of shark, the film crew used water-level shots from the “shark’s perspective”, and some live footage of real sharks. Then in the final “battle” scene, they finally had a working shark. But, as I said before, animatronics are not so revolutionary nowadays. Today we can animate a shark that might as well be on the other side of the aquarium glass, it looks so real (even Sharknado looked better than old Brucey). But at the time, that shark was pretty darn impressive.

So what did this disaster of an effects team do for the movie? It made it iconic. What’s more intimidating than a bad guy that you don’t see until the end of the movie? By the time you’ve sat through an hour of knowing that it’s lurking in the ocean below, it doesn’t actually matter how scary it really looks. You just know that you’ve been afraid of it for the last hour and here it is right in front of you with no warning. And throw in the fact that it at least looked like it might have been a real shark – that’s some scary sh** right there (once again, not an adjustment, that’s exactly how I turned in my essay. My professors all hate my sass, I’m sure).

So what did this disaster of an effects team do for the movie? It made it iconic. What’s more intimidating than a bad guy that you don’t see until the end of the movie? By the time you’ve sat through an hour of knowing that it’s lurking in the ocean below, it doesn’t actually matter how scary it really looks. You just know that you’ve been afraid of it for the last hour and here it is right in front of you with no warning. And throw in the fact that it at least looked like it might have been a real shark – that’s some scary sh** right there (once again, not an adjustment, that’s exactly how I turned in my essay. My professors all hate my sass, I’m sure).

As much as I love poking fun at outdated effects and overused themes, there is one thing about Jaws that is not outdated, and that’s the concept. Sharks are still scary. I myself don’t like to swim in the ocean, because I do fear the highly unlikely phenomenon that my small body will be dragged to the  depths by a Great White. That, or I’ll brush some seaweed with my foot – two equally frightening fates. But the fact is that a majority of Americans are afraid of sharks. I’m not quite sure where this fairly irrational fear comes from, but it is most definitely irrational. According to data accumulated by the Huffington Post in honor of Shark Week (here’s a thought: how are so many people afraid of sharks but still love Shark Week?), the odds of being attacked by a shark are 1 in 11.5 million. You have a better chance of dying in your own bathtub. But, despite this fact, Spielberg’s film played on the very real fear of being attacked by a shark, and used it to strike fear in the hearts of millions.

depths by a Great White. That, or I’ll brush some seaweed with my foot – two equally frightening fates. But the fact is that a majority of Americans are afraid of sharks. I’m not quite sure where this fairly irrational fear comes from, but it is most definitely irrational. According to data accumulated by the Huffington Post in honor of Shark Week (here’s a thought: how are so many people afraid of sharks but still love Shark Week?), the odds of being attacked by a shark are 1 in 11.5 million. You have a better chance of dying in your own bathtub. But, despite this fact, Spielberg’s film played on the very real fear of being attacked by a shark, and used it to strike fear in the hearts of millions.

The other timeless point in this movie is the way that Spielberg creates suspense. While his lack-of-shark was kind of a happy accident, the other parts of the movie that give you chills and make you jump are completely credited to Spielberg’s genius. As I said earlier in reference to the fact that the climax comes when the shark appears without musical warning, there is as much benefit to taking away something as there is to adding it, as far as movies are concerned. One of the most suspenseful things that Spielberg does in this movie (aside from all of the actual shark stuff) is create silence. Particularly in the scenes when the shark attacks have already happened, a lack of music creates a feeling of unease that can’t really be shaken.

To me, the most unnerving part of the whole film is when the bloody raft washes up on shore (the scene above). This is a psychological move that has Spielberg written all over it. The scene takes place on the beach, with a nervous Chief Brody watching the kids in the water. One boy is apart from the others in the water, and the camera flips to the shark’s perspective to see the raft is his target. Suddenly the playful screams are interrupted by one of fear, and the other kids are frightened and confused by the suddenly blood-red water surrounding them. The scene becomes chaotic as parents rush to collect their kids and get them out of the water. When it seems that everyone is safe on land, one mother is still searching for her son. She calls his name a few times, and then you see the raft, torn to shreds, wash ashore among a red cloud in the water. The music has stopped and all you hear is the sound of the waves on the beach, and the scene fades. I shivered just writing that paragraph.

And how could I leave out, my very favorite part of all thrillers: the jump scares (imagine an eye roll in there somewhere). No scary movie would be complete without them, and they never really get old. It doesn’t really matter how many times we’ve seen the movie, my mom and I both drop whatever’s in our hands when that head comes out of the shipwreck. Suspense is great and everything, but sometimes it’s the lack of suspense or buildup that has the greatest impact on a moviegoer’s experience.

And how could I leave out, my very favorite part of all thrillers: the jump scares (imagine an eye roll in there somewhere). No scary movie would be complete without them, and they never really get old. It doesn’t really matter how many times we’ve seen the movie, my mom and I both drop whatever’s in our hands when that head comes out of the shipwreck. Suspense is great and everything, but sometimes it’s the lack of suspense or buildup that has the greatest impact on a moviegoer’s experience.

I would like to conclude this argument by saying that, despite appearances, I am in no way showing any kind of disrespect to Jaws. I think I made it clear that I have the utmost respect for Steven Spielberg as a director, but I would also like to make it clear that Jaws is a classic for a reason. It’s not always a given that, just because millions of people saw it, it was a good movie – cough cough, Avatar, cough cough – but in this case, the 67 million alone can speak to it’s quality. The real telling factor, however, is that fact that since its release, Jaws has retained a spot on the Billboard highest-grossing movies list. Millions of people will go out to see a bad movie, but millions of people will not continue to watch a bad movie over and over again.

Although the theme has been stretched to its limit and the shark was never really all it was cracked up to be, Jaws is still a relevant thriller movie and deserves its title as a classic.